Para leer esta historia en Español, por favor escribame a steph.alarcon@gmail.com y trataré traducirla!

This past winter, I spent a month in Guatemala studying Spanish, checking out appropriate technology projects, and zipping around the geologically manic country around the Western Highlands. Here’s a reportback from a visit to the offices of the Appropriate Infrastructure Development Group (AIDG). I got to check out some prototype wind and solar designs and take a peek at their new kit-built CNC machine and custom circuit board designs. Later, I got to poke around the office and come along on a site visit to a biodigestor installation they did outside of the city. It lets the farmers nearby turn animal waste into organic fertilizer and cooking gas while reducing greenhouse emissions. I got to hear about the combination of technical and user friendliness challenges they encountered and saw how the system is working now that it’s been tweaked a few times. Pretty cool stuff.

I was based in a dignified, culture-rich medium sized city called Quetzaltenango if you go by the map, but everyone calls it Xela (SHAY-la). The legend goes that before the Spanish crashed the party, the Mam Maya inhabitants called the place Xelaju, or Under 10 Mountains. When the Spanish arrived, they had Nahuatl-speaking “helpers†from Mexico in tow. They called the place Quetzaltenango, or City With That Adorable Green And Red Bird Whose Splendiferous Tailfeathers Are Used as Currency. I’m paraphrasing, but you get the drift.

One reason I was really amped to go to Xela was to check out the work of AIDG. AIDG is a Boston-based NGO that works in Guatemala and Haiti. When I visited, the Xela office was in transition to a new, completely-Guatemala based organization called Alterna, whose focus will be business incubation. They are so new their website isn’t even done yet. In Guatemala, AIDG runs competitions for green business plans and does business incubation. They helped launch XelaTeco, a company that has since folded to reorganize, but not before doing several microhydro and solar installations. I visited one such installation, which I’ll cover in another post.

I had a great conversation with Steve Crowe, the Guatemala program director about what they’re up to and whether hackerspaces back in the states might be useful collaborators. I got a chance to snoop around the office and check out some prototype projects.

This lovely specimen is a solar refrigerator. On top of the frame is a photovoltaic panel that also shades the rest of the gear. The geometric-looking thing is a heat exchanger made of copper pipe and aluminum fins. At the bottom you can see a cooler where you’d store whatever you want to keep cold.

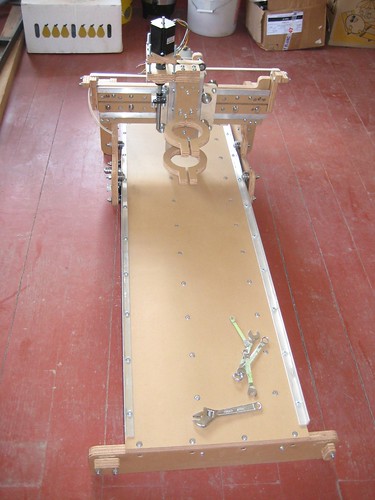

This is an experiment with a low-cost wind turbine. They also have cool toys like this almost-assembled CNC machine from a kit.

And they have an enviable workshop. Check out the tool cabinet with blackboard paint! That makes so much sense. Tablesaw and solar panels…pitter patter.

I went back another day to meet up with José Ordoñez, the Guatemala technology lead. We went on a site visit to a small farming community a little bit outside the city. AIDG had installed a biodigester and cooking gas hookup that was serving two households, with a third about to be connected.

The shiny stuff in the foreground of this shot of one of Xela’s ten peaks is the end of this season’s corn harvest. Corn was ubiquitous in every place I visited except for the most built-up urban areas.

The goal of the biodigester is the same as any biodigester attached to farmland: It takes animal poop and turns it into fuel and fertilizer. It’s kind of like homebrewing actually, in that the magic is in the digestion (fermentation) of the waste by microorganisms. You use it by putting animal waste in one side, let it decompose and ferment in an inner bladder or chamber from which the offgassed methane is collected, then at the other end the processed waste is used as organic fertilizer. I was surprised how many times I saw small roadside farms selling abono organico, or organic fertilizer. This system has another clever environmental advantage: reducing agricultural greenhouse gases. Methane is a much worse greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, so it’s actually better to burn it if it’s being produced anyway. Might as well burn it at a stove.

In this shot, you can see José standing next to the first leg of the pipe hookup that sends the methane to nearby houses. The beige tubing is where the methane exits the bladder. The little roof on top of the cinder block structure is heavy enough to push down on the bladder, providing the pressure needed to make a nice substantial cooking flame.

We poked around at the tank and the fittings, then we walked over to two of the homes. The cooking gas connection into the houses is just 1″ or so PVC pipe. Before chatting with the people using the gas, José told me that they’d tried a few resource-sharing models that hadn’t quite worked. They started the build-out about a year and a half ago and had been tweaking it for about 15 months of that time.

At first, the idea was to build a communal kitchen that three or four families would use. So they put the gas stove in a central location.

That totally didn’t work.

The cooks struggled under the burden of carrying all their cooking supplies to the stove. I don’t blame them. I hate bringing a couple spices when I cook at friends’ houses. I would be super annoyed if I had to lug gallons of water and pounds of corn and beans from my kitchen to a neighbor’s place to cook.

Then there was the wind problem. The flame wasn’t protected well and it constantly went out and burned ineffeciently. The families complained that they were getting about 15 minutes of cooking per day.

Then the families got one or two more farm animals that upped the waste that went into the digester and increased their fuel output, and that definitely helped. But what really made peace on the homestead was that they plumbed the cooking gas into each house. That leveled up the user friendliness by about a million. Now that two families have methane burners in their kitchens, they say they’re getting about two hours of gas per day. That has drastically cut down their propane bills. Check out the custom locally-welded cooktop and that lovely blue flame!

It’s still a shared resource, though. There is a third household waiting to get its own cooking gas hook up, but in the meantime, the heads of the three households share the gas by trading off days. Doña Flor might use it Monday and Tuesday, Doña Doris has dibs Wednsday and Thursday, while Doña Laura gets the cheese over the weekend.

José and I talked about watershed management, environmental education, community radio, welding and brazing, and even an idea for using local litter as a building material. Guatemala has rudimentary trash collection at best and lacks good landfill and recycling infrastructure. Plastic bags and bottles line many waterways in this mountainous land where gravity always wins. I was really troubled by this because it’s not like soda bottles and tattered plastic bags are good reuse candidates like metal, wood, and brick. But José challenged me on that. Apparently there’s a way to shove plastic bags really tighly into soda bottles and use them as bricks if you use enough mortar. That one had completely slipped by me and it was an awesome reminder that optimism and creativity are a killer combination that can take on really tough tasks.

In this shot, you can see José standing next to the first leg of the pipe hookup that sends the methane to nearby houses. The beige pipe is where the methane exits the bladder. The little roof on top of the cinder block structure is heavy enough to push down on the bladder, providing the pressure needed to provide a nice solid cooking flame.

We poked around at the tank and the fittings, and then we walked over to two of the homes. The cooking gas connection into the houses is just 1†or so PVC pipe. Before chatting with the people using the gas, José told me that they’d tried a few resource-sharing models that hadn’t quite worked. They started the build-out about a year and a half ago and had been tweaking it until last August.

At first, the idea was to build a communal kitchen that three or four families would use. So they put the gas stove at a central location.

It totally didn’t work.

The cooks struggled under the burden of carrying all their cooking supplies to the stove. I don’t blame them. I hate bringing a couple spices when I cook at friends’ houses. I think I would be super annoyed if I had to lug gallons of water and pounds of corn and beans from my kitchen to a neighbor’s place to cook.

Then there was the wind problem. The flame wasn’t protected well and it constantly went out and burned inefficiently. The families complained that they were getting about 15 minutes of cooking per day.

Then the families got one or two more farm animals that upped the waste that went into the digester and increased their fuel output. But what really made peace on the homestead was that they plumbed the cooking gas into each house. This leveled up the user friendliness by about a million. Now that two families have methane burners in their kitchens, they say they’re getting about two hours of gas per day which has drastically cut down their propane bills. Check out the custom locally-welded cooktop and that

Hey,

Awesome to see your report on AIDG. I’ve something for you on the note of hackerspaces collaborating with organizations like AIDG on Appropriate Technology Development. The hackerspace I am part of, Makers Local 256, has been collaborating with the local Huntsville chapter of Engineers Without Borders to run an Appropriate Technologies Lab in the space. So far, we’ve been developing some project concepts for agriculture and water access. Check out our lab’s wikipage:

https://256.makerslocal.org/wiki/index.php/Appropriate_Technologies_Lab

– Ethan Chew/spacefelix, Makers Local 256